|

IPN Opinion article

Authors:

Indur M. Goklany

Media outlet:

The Monitor (Uganda)

World Population Day: The problem is not population, but poverty.

For many groups like the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) World Population Day on July 11 was another chance to bemoan 'the relentless growth in human population,' while the United Nations Population Fund says 'stabilising population would help sustain the planet.' The problem, however, is not population but poverty.

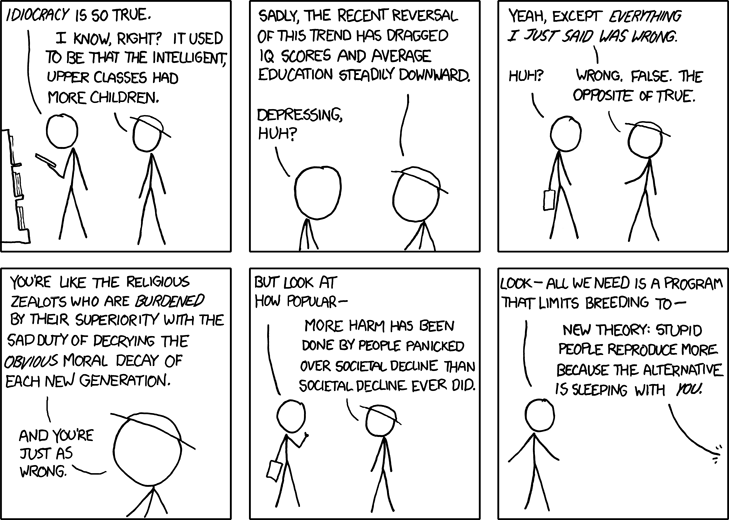

Over-population enthusiasts have always claimed there is not enough land or resources for everyone and, even as their predictions of apocalyptic famines, epidemics and shortages failed to come true, they gained support from many environmentalists.

Exponentially increasing wealth, population and technology, they allege, will cause pollution, climate change and irreversible losses of biodiversity, pushing the Earth to a tipping-point, threatening humans and the planet itself.

On the contrary, our lives are now longer, wealthier and healthier.

At early stages of development, societies give priority to acquiring wealth over environmental protection, to get basic needs and wants like food, shelter, health, education and material goods. But, once these are met, societies soon have the desire and, importantly, the wealth and technology to solve environmental problems.

What is more, evidence indicates that as countries grow richer, their population growth slows. The global population growth rate, far from rising exponentially, has tumbled since the 1960s.

Recent projections expect population to peak this century, around nine billion.

Initially, growth and technology do increase population as better health care, sanitation and nutrition cut deaths.

But, in the long run, births fall, for example through better education and work opportunities for women.

Although the world population has quadrupled since 1900, food, energy and raw materials are cheaper today than for much of history. Agricultural technology and trade have made food more affordable and available around the world.

In the early 1970s, 37 per cent of the developing world's people suffered from chronic hunger but it is now down to 17 per cent, despite ill-advised biofuel subsidies which divert food to fuel.

The combination of increased prosperity, trade and technology has lowered the lower real prices of food and many raw materials, effectively making them less scarce. Food and metals are now eight times cheaper in India than in 1900, and thirteen times cheaper in the USA.

Basic hygiene, cleaner water, sanitation, more food and developments in medicine such as vaccinations and antibiotics have reduced mortality for infants, children, mothers and everyone else. Consequently, global average life expectancy, perhaps the single most important measure of human well-being, increased from 31 years in 1900 to 47 years in the early 1950s to 67 years today.

Hybrid seeds and other advances in agricultural technology (like fertilisers, irrigation and pesticides) have saved vast acres of forests and wildlands from conversion to farmland. In the USA, for example, despite the population tripling and consumption increasing 19-fold, cropland has remained steady at 330 million acres since 1910: technology actually saved about 1,300 million hectares. Though air quality in newly industrialising countries is much worse than in rich countries, they are making quicker improvements than developed countries did in the latter half of the 20th century.

China, India and South Africa, like Although carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have not peaked, the quantity of emissions per dollar of Gross Domestic Product (literally, the carbon intensity of wealth) has peaked and is falling rapidly in many places.

But many environmentalists and population enthusiasts want to restrict economic growth, technology and human freedoms, damaging both humans and the environment.

Billions in developing countries still suffer from poverty and its consequences such as hunger and malaria. They must be allowed to improve their lives.

Indur Goklany is author of The Improving State of the World (Cato, 2007) and co-editor of the peer-reviewed Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development (EJSD).

|